Development of the Modern Health Insurance Industry Peer Reviewed

Abstruse

Inquiry shows consolidation in the private health insurance industry leads to premium increases, even though insurers with larger local market place shares generally obtain lower prices from health intendance providers. Boosted research is needed to sympathise how to protect confronting harms and unlock benefits from scale. Information on enrollment, premiums, and costs of commercial health insurance—by insurer, plan, customer segment, and local market—would help us empathise whether, when, and for whom consolidation is harmful or beneficial. Such transparency is mutual where there is a potent public interest and substantial public regulation, both of which characterize this vital sector.

INTRODUCTION

The public interest in ensuring competitive, robust private wellness insurance markets has never been greater. Today, almost two-thirds of the U.S. population under historic period 65 is enrolled in a private comprehensive health program.1 Individual insurance is as well playing an increasingly of import role in supplying coverage to Americans in public programs, including Medicaid, which has experienced a rapid increase in enrollment every bit a consequence of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Those who lack coverage and are ineligible for public coverage must purchase private policies to comply with the ACA'southward individual mandate.

At the same fourth dimension, private insurance premiums ($16,834 for the average family) and out-of-pocket spending ($800 per person) are high and projected to grow. Federal subsidies for individuals purchasing plans in the ACA's insurance marketplaces, meanwhile, are projected to total $37 billion in 2015 and reach $87 billion by 2020.2,3

Given these stakes, there is a substantial public benefit to critically evaluating any significant changes in markets for private wellness insurance. This upshot brief, based on my extensive review of public information and the economics research literature, examines consolidation in the wellness insurance industry and its impact on premiums and other outcomes of interest to consumers. I as well consider how to assess the potential effects of future merger proposals.

MARKET CONCENTRATION IS HIGH AND INCREASING

Commercial Insurance

Roughly 175 million Americans nether age 65 purchased private insurance through their employers or the individual insurance market in 2013, the most contempo year for which data are bachelor.4 The industry has expanded since the ACA'due south marketplaces went online in 2014.

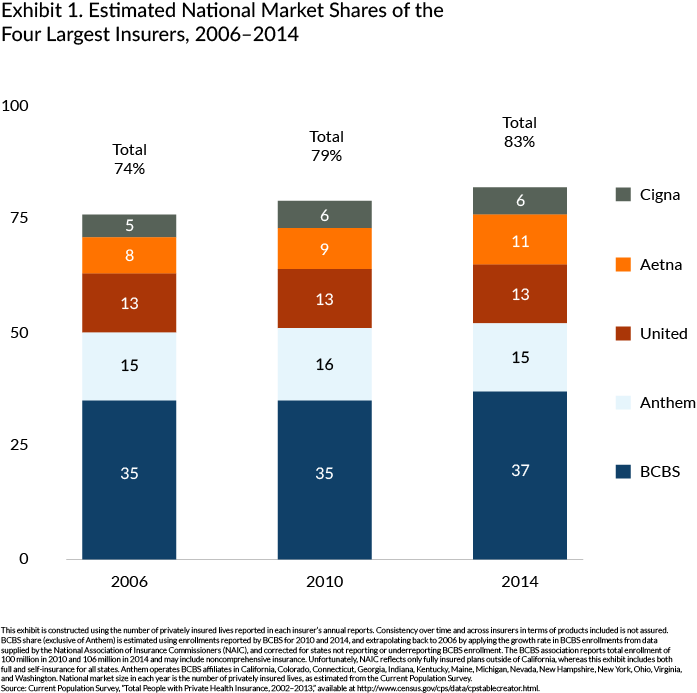

Showroom one contains gauge estimates of the national market share of the four largest insurers over the period 2006–2014. With a few exceptions, Bluish Cross Blue Shield (BCBS) affiliates have sectional, nonoverlapping market territories and hence do not compete with one another. All 36 BCBS affiliates are therefore treated as a single house for purposes of constructing the national four-firm concentration ratio (the sum of marketplace shares for the leading 4 firms), although marketplace shares for the for-profit Bluish plans (all operated by Anthem, Inc., and spanning 14 states today) are denoted separately in the exhibit.

Betwixt 2006 and 2014, the four-firm concentration ratio for the auction of individual insurance increased significantly, from 74 percent to 83 pct. Past comparison, the 4-firm concentration ratio for the airline manufacture is 62 percent.v

Exhibit one does not necessarily reflect the degree of concentration in insurance markets that are relevant to most consumers, however. Many wellness plans have a significant local, but not national, presence—Kaiser Permanente, Intermountain, and Geisinger among them. The degree of competition in whatsoever product and geographic market depends on the market participants and the characteristics of the products they offering. The American Medical Association'south annual reports containing detailed market place share information for the peak two insurers prove that concentration is higher inside metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), on average, than in the nation as a whole. Moreover, this concentration appears to exist increasing over time.6

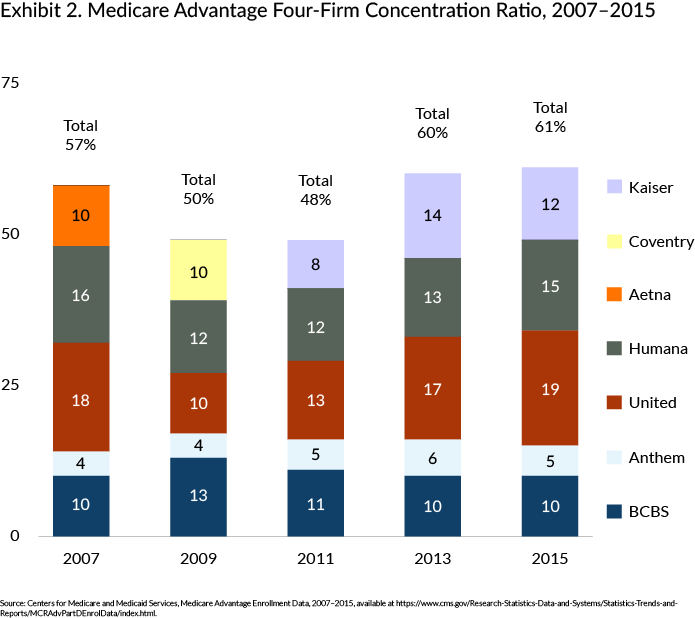

Medicare Advantage

Nigh 22 million Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in authorities-financed private plans, collectively known equally Medicare Advantage. Showroom 2 shows a 13-percentage-point growth between 2011 and 2015 in the combined market shares of the four leading Medicare Advantage insurers. This market has experienced significantly more turbulence than the private insurance sector, attributable to myriad changes in regulations and reimbursement rules.vii The national market leaders for Medicare Advantage differ somewhat from those in the private insurance market (which pools together fully and self-insured plans) simply are the aforementioned for fully insured employer-sponsored plans. I judge that 37 pct of Medicare beneficiaries live in counties where the Medicare Reward market place would be deemed "highly concentrated," per the Department of Justice and the Federal Merchandise Commission.8

Drivers of Industry Consolidation

Virtually insurance manufacture consolidation in the past xx years has been driven by mergers and by growth in the BCBS affiliates' market shares.ix These mergers tin can be categorized as:

- attempts by regional insurers to gain broader service areas;

- attempts past national insurers to obtain a presence in virtually all geographic areas;

- acquisitions of local HMOs and provider-sponsored plans by incumbents; or

- the consolidation of for-turn a profit BCBS affiliates (into Anthem).

Some contend that recent or proposed insurance mergers are the event of the Affordable Intendance Act, just consolidation was already well nether mode earlier the law's passage. To the extent such consolidation is anticompetitive, it is at cross-purposes with the ACA. Every bit Thomas Greaney, an expert on wellness care and antitrust law, recently observed, the ACA "does not regulate prices.... Instead the law relies on (1) competitive bargaining betwixt payers and providers and (2) rivalry within each sector to bulldoze cost and quality to levels that best serve the public."ten

In fact, the ACA promotes competition in the insurance industry. For case, through regulatory reforms, the law fosters standardization of products and certifies plans, which reduce the hurdle to entry posed by the need to establish a credible reputation. The health insurance marketplaces, meanwhile, reduce marketing and sales costs, thereby raising the likelihood of entry. In fact, the marketplaces were explicitly designed to facilitate competition among insurers.

WHAT Accept WE LEARNED FROM CONSOLIDATION IN THE PAST?

Mergers lead to reduced payments to providers, only the cost savings are non passed through on boilerplate. There is limited evidence regarding the impact of consolidation on wellness plan quality.

Wellness intendance provider prices

Several health economists have studied the correlation between hospital prices and market competitiveness, typically measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman alphabetize, or HHI (see box).11 Although the HHI is an imperfect proxy for truthful competitiveness (the degree to which firms vie to serve consumers through product design, price, service, etc.), at that place are no alternative straightforward measures. Studies of hospital price and insurance HHI, which utilise different data sources and look at different time periods, generally find hospital prices are lower in geographic areas with higher levels of HHI—that is, where there is higher insurance marketplace concentration. This relationship besides holds when researchers study changes over time: in markets that are becoming more full-bodied, there is slower growth in infirmary prices.

HHI: A Standard Measure of Market Concentration

The Herfindahl-Hirschman Alphabetize (HHI) is used past the Antitrust Segmentation of the U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission to evaluate the potential antitrust implications of acquisitions and mergers beyond many industries, including health care. It is calculated past summing the squares of the marketplace shares of individual firms.

Markets are classified as ane of three categories: 1) nonconcentrated—HHI below 1,500; 2) moderately concentrated—HHI between 1,500 and 2,500; and 3) highly concentrated—HHI above 2,500.

Sources: U.S. Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission, "Horizontal Merger Guidelines," Aug. 2012.

But lower prices for health care services will benefit consumers merely if they are ultimately passed through to consumers, in the class of lower insurance premiums or out-of-pocket charges. Even if price reductions are realized and passed through, if they are achieved as a result of monopsonization of health intendance markets, consumers may experience an offsetting damage. Monopsony—in which a large buyer, rather than seller, drives prices down—is the mirror image of monopoly; lower input prices are accomplished by reducing the quantity or quality of services beneath the level that is socially optimal.12

A written report of the 1999 Aetna–Prudential merger found a relative reduction in health care employment and wages in those geographic areas where there was more substantial market overlap between the 2 insurers.13 The implication is that the exercise of market power over health care providers reduced prices and output—the authentication of monopsony.

Even so, in settings where both sides possess market ability and bargain over prices, an increase in buyer ability tin can reduce price without reducing output (or, equivalently, without leading to a deterioration in quality). Indeed, two other studies of monopsony focusing on hospitals—an industry that is concentrated in many areas—observe areas with higher insurer HHIs (higher concentration) accept higher, non lower, infirmary utilization.14,fifteen

Health care quality

Little published inquiry exists on the link between consolidation and plan quality. The most relevant written report to date, which pertains to the Medicare Advantage market place, found that the availability of prescription drug benefits (before the enactment of Part D) was higher in areas with more rivals, all else equal.16 There is a vast literature concerning other wellness care settings that shows quality does not ameliorate when markets become more consolidated.17 Although quality is more difficult to evaluate than price, the competitive mechanisms linking macerated competition to higher prices operate similarly with respect to lower quality.

Insurance premiums

Several studies document lower insurance premiums in areas with more insurers. These studies span a multifariousness of segments, including the public wellness insurance marketplaces, the large-group marketplace (cocky-insured and fully insured plans combined), and Medicare Advantage.18,19,20 One recent study suggests premiums for self-insured employers are lower where insurer concentration is higher, but premiums for fully insured employers are higher.21

The all-time available evidence on the impact of consolidation comes from what are known as "event studies" or "merger retrospectives," such as the aforementioned Aetna–Prudential merger study. The researchers on that study found that premiums (for a pooled sample of self-insured and fully insured large-group plans) increased significantly more in areas with greater pre-merger market overlap. Moreover, the premium increase was not limited to the merging insurers; rival insurers raised premiums every bit well (in areas where the merging firms had substantial overlap). This is particularly notable in calorie-free of the fact that following the Aetna–Prudential merger, health care employment and wages were reduced. The price savings were not passed on to consumers.

A 2nd report examined the impact of the 2008 merger of Sierra Wellness and UnitedHealth on small-group premiums in ii Nevada markets. As compared with control cities in the South and Westward, small-group premiums in these markets increased by 13.seven percent the yr following the merger.22

Consolidation-induced premium increases generally have not been commencement by competition from new entrants to private health insurance markets. Instead, entry into a given marketplace has tended to occur through acquisition. New firms seeking to enter a market face a number of substantial challenges, including those related to:

- building networks of local providers and negotiating competitive reimbursement rates;23

- establishing a credible reputation with expanse employers and consumers;

- developing relationships with brokers, who serve every bit intermediaries for most purchasers; and

- achieving economies of calibration in information engineering science, disease management, utilization review, and customer-service related functions.

In light of these and other impediments, consolidation even in nonoverlapping markets reduces the number of potential entrants that might attempt to overcome price-increasing (or quality-reducing) consolidation in markets where they do non currently operate.

THE ACA DOES Not DIMINISH THE Demand FOR INSURANCE MARKET Contest

Effects of contest

A reasonable question to ask is whether the experience of the Aetna–Prudential and UnitedHealth–Sierra Health mergers is informative in light of the significant recent changes brought nigh by the ACA. Early evidence suggests that contest continues to accept salutary effects on health insurance markets, even in the post-ACA world. One study institute that premiums on the individual exchanges in 2014 were more than 5 percent college post-obit the determination by a large national insurer non to participate in federally facilitated exchanges that year.24 In another study, researchers estimated that having an additional insurer in a given ratings area results in premium savings of well-nigh $500 per individual.25

Medical loss ratio regulations

The ACA provision most relevant to the bailiwick of insurer consolidation and its consequences concerns medical loss ratios (MLRs). As of 2011, insurers must devote at least 85 percent or fourscore per centum of premium revenues, cyberspace of taxes and licensing fees, to medical claims and quality improvement for their fully insured lives; the college floor pertains to large-group customers while the lower floor applies to pocket-sized groups and individuals. Insurers failing to satisfy these requirements must refund the shortfall to enrollees. Some have argued that these regulations mitigate concerns over potential anticompetitive consequences of consolidation in this sector.26 This argument is non convincing, however, for at least 5 reasons:

- More than than one-half of privately insured enrollees are in self-insured plans, and the minimum MLR regulations practise not pertain to these plans.

- The MLR regulations try to cap manufacture profits simply do not protect consumers from postmerger harm resulting from loss of contest on dimensions other than the share of spending devoted to medical claims and quality improvement activities. Such dimensions include innovative benefit designs, breadth and quality of provider networks, responsiveness of customer service, and quality of chronic disease direction programs. Reducing the competition (or potential contest) via a merger may relax or eliminate competition on these dimensions.

- For the MLR regulations to mitigate the adverse effects of consolidation, statutory floors must exceed the MLRs that would otherwise prevail. However, a recent written report reports national MLRs for 2013 were 86 percent, 84 percent, and 89 percent for the individual, pocket-sized-grouping, and big-group markets, respectively.27 These findings suggest there may exist substantial room for profitable merger-related price increases in the private market in particular, notwithstanding the minimum MLR requirement.

- The MLR regulation could be gamed in a diversity of ways past relabeling profits as costs. For example, insurers with ownership stakes in health care facilities and provider organizations could accommodate internal transfer payments to these groups to ensure MLR minima are satisfied. Similarly, many insurers engaging in quality improvement efforts could create a separate quality improvement arm and charge the insurance arm fees that offset profits in excess of the MLR minima.

- The minimum MLR regulation could be repealed. If transactions that would otherwise be deemed anticompetitive are not challenged under the belief that the regulation acts as a check on postmerger margin increases, what happens if a more than consolidated insurance industry successfully argues for its repeal?

Consolidation may enable insurers to implement or expedite productivity-enhancing changes to the health care delivery system, but this potential benefit remains speculative.

The recent shift toward paying for value, rather than volume, of health care services will require significant changes in how insurers pay providers and how providers deliver and organize care. Some insurers have suggested that mergers will raise their ability to develop and implement new value-based payment agreements.28 But as yet in that location is no evidence that larger insurers are more likely to implement innovative payment and care management programs. Moreover, a countervailing forcefulness offsets the incentive to invest in such changes, fifty-fifty if scale reduces the costs of doing so: ascendant insurers in a given insurance market place are less concerned with the possibility of ceding market share.

Some other open question is whether the benefits of scale in this regard pertain not simply to combinations in the same relevant market only likewise to combinations across different insurance markets, that is, across different segments in the same geographic expanse or across different geographic areas in the same segment. For instance, some have suggested that insurers with a broader geographic footprint volition face lower per-enrollee costs for implementing value-based agreements. Still, in actuality, national insurers may face up greater difficulty in implementing new payment or care management models across disparate markets than local payers would face implementing such programs in a unmarried area. This reality may explain why concerted delivery arrangement reform efforts have tended to emerge from other sources, such as provider systems and state- or locally based payers like Massachusetts Blue Cantankerous and Blue Shield.

Finally, the oft-repeated claim that some insurers will not be able to replicate or admission value-based payment without a merger should exist treated with skepticism. Efficiencies must be merger-specific and verifiable if they are to be credited against potential harm arising from diminished competition, and the question remains whether benefits volition be passed through to consumers. Moreover, any brusque-term gain from avoiding evolution costs for value-based programs may be kickoff by a reduction in long-term benefits arising from competition among insurers to develop better versions of these programs.

ROLES OF ENFORCERS, POLICYMAKERS, AND RESEARCHERS GOING FORWARD

Some observers assume that federal and state antitrust enforcers will challenge transactions that are not likely to exist benign to consumers. All the same, these agencies file conform if their investigations propose that the transaction will "lessen competition" or "tend to produce a monopoly," per Section 7 of the Clayton Act. Ascertaining whether a transaction violates this central competition statute is a different matter from ascertaining whether it is in the public interest. For example, a merger that is probable to lead to price increases without offsetting benefits to consumers may not violate Department 7 if it cannot be shown that the merger lessens contest in a relevant antitrust market. Different stakeholders might also place dissimilar weights on the potential losses and gains for various affected parties.

Given the significance of the insurance sector to our wallets and to the functioning of our health intendance organization, the public deserves ameliorate information with which to evaluate these transactions and the manufacture more generally. Equally a start, avenues must be found for requiring detailed reporting, at a local level (such equally by nada code), on insurance enrollment, plan design, premiums, and medical loss ratios for every commercial health plan on offer. This reporting would ideally include cocky-insured plans, as more than one-half of the privately insured are enrolled in these types of plans. With these data, policymakers, researchers, and regulators would exist able to monitor market developments and to intervene, if necessary, based on amend and timelier information.

Acknowledgments

The writer cheers Chris Ody and Victoria Marone, both of Northwestern Academy, for their aid in preparing this brief and Zack Cooper, David Cutler, Mark Duggan, Pinar Karaca-Mandic, and Mark Shephard for their helpful comments.

This issue brief was adapted from: L. S. Dafny, Testimony Before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Antitrust, Competition Policy, and Consumer Rights, on "Health Insurance Manufacture Consolidation: What Practise We Know from the Past, Is It Relevant in Calorie-free of the ACA, and What Should We Ask?" September 22, 2015.

Notes

one National Center for Health Statistics, "Early Release of Selected Estimates Based on Data From the National Wellness Interview Survey, 2014," Table 1.2b (Hyattsville, Md.: NCHS, June 2015), http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/earlyrelease201506.pdf.

2 Kaiser Family Foundation and Health Research and Educational Trust, 2014 Survey of Employer Health Benefits (Menlo Park, Calif., and Chicago: Henry J. Kaiser Family unit Foundation and HRET, Sept. 2015), http://kff.org/wellness-costs/report/2014-employer-health-benefits-survey; Wellness Care Cost Institute, 2013 Health Care Cost and Utilization Study (Washington, D.C.: HCCI, October. 2014), https://www.healthcostinstitute.org/images/pdfs/2013-HCCUR-12-17-14.pdf.

3 Congressional Upkeep Function, Insurance Coverage Provisions of the Affordable Intendance Human action—CBO's August 2015 Baseline (Washington, D.C.: CBO, Aug. 25, 2015), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/45069.

iv Per the U.S. Census Agency's 2013 Current Population Survey (CPS) Annual Social and Economic (ASEC) Supplement, Tabular array HI01, https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/cps-hi/hi-01.2013.html.

v U.S. Department of Transportation, Bureau of Transportation Statistics, "Airline Domestic Marketplace Share July 2014–June 2015," (Washington, D.C.: DOT), http://www.transtats.bts.gov/.

6 The American Medical Association reports are not strictly comparable over time because of changes in the number of MSAs included, and the inclusion of self-insured lives. The figures for 2012 include self-insured lives.

7 Total enrollment in Medicare Advantage has increased significantly over this menses, from ix.three meg in 2007 to 22 1000000 in 2015. Duggan, Starc, and Vabson evidence that reimbursement is strongly linked to entry. They estimate that for every dollar of additional reimbursement from the Medicare program, 20 cents is passed through to enrollees in the form of better coverage. M. Duggan, A. Starc, and B. Vabson, "Who Benefits When the Authorities Pays More? Laissez passer-Through in the Medicare Advantage Programme," No. w19989 (Washington, D.C.: National Bureau of Economic Research, March 2014), http://www.nber.org/papers/w19989.

8 U.Southward. Section of Justice and Federal Merchandise Commission, Horizontal Merger Guidelines (Washington, D.C.: DOJ and FTC, 2010), http://www.ftc.gov/os/2010/08/100819hmg.pdf.

9 This growth precedes the period depicted in Showroom ane. Per Ginsburg, "the relative position of the Blues strengthened with the loosening of managed care because of the diminishing importance of HMOs, which were generally a weak point for the Dejection. Blue plans' ability to negotiate lower rates with providers on the basis of their big market share became more important." P. Ginsburg, "Competition in Health Intendance: Its Development Over the By Decade," Health Diplomacy, Nov.–Dec. 2005 24(half dozen):1512–22.

10 T. L. Greaney, "The Land of Competition in the Health Care Marketplace: The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Deed'southward Touch on on Competition," United States House of Representatives Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law, Sept. 10, 2015, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-114hhrg96053/html/CHRG-114hhrg96053.htm.

11 G. A. Melnick, Y. C. Shen, and 5. Y Yu, "The Increased Concentration of Health Programme Markets Can Do good Consumers Through Lower Hospital Prices," Health Affairs, Sept. 2011 thirty(ix):1728–33; A. Southward. Moriya, W. B. Vogt, and Grand. Gaynor, "Hospital Prices and Market Construction in the Infirmary and Insurance Industries," Health Economics, Policy and Police force, Oct. 2010 v(four):459–79; and E. E. Trish and B. J. Herring, "How Practice Wellness Insurer Marketplace Concentration and Bargaining Ability with Hospitals Affect Health Insurance Premiums?" Periodical of Health Economics, July 2015 42:104–14. All three rely on estimates of insurer HHI calculated from InterStudy data. Melnick et al. find that hospital prices in 2001–2004 are lower in MSAs with higher insurer HHI, provided the insurer HHI exceeds 3,200. Moriya et al. notice that increases in MSA-level insurer HHI between 2001 and 2003 are associated with decreases in hospital prices. Trish and Herring utilize more recent data (from 2006 to 2011) and discover that hospital prices are lower amidst more than concentrated insurance markets. United states of america House of Representatives, Commission on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law, Sept. 10, 2015, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-114hhrg96053/html/CHRG-114hhrg96053.htm.

12 The fashion in which a monopsonistic insurance sector would reach lower reimbursement rates is by setting a depression market place reimbursement rate, 1 which is below the value that some consumers identify on those services. That is, there will be excess demand by consumers for services at this rate, and the monopsonist does not permit cost to rising to expand output and equilibrate demand and supply.

thirteen L. Dafny, Thousand. Duggan, and S. Ramanarayanan, "Paying a Premium on Your Premium? Consolidation in the U.Due south. Health Insurance Industry," American Economic Review, Apr 2012 102(2):1161–85.

14 Feldman and Wholey nowadays testify that prices are lower, but infirmary utilization (a mensurate of quantity) is higher in markets with less competitive insurance markets. Similarly, McKellar et al. find in more concentrated insurer markets, health care prices are lower, utilization is higher, but overall spending is lower. R. Feldman and D. Wholey, "Do HMOs Have Monopsony Power?" International Journal of Health Care Finance and Economic science, March 2001 one(1):7–22; and Thousand. R. McKellar, S. Naimer, Chiliad. B. Landrum et al., "Insurer Market place Construction and Variation in Commercial Health Care Spending," Wellness Services Enquiry, June 2014 49(3):878–92.

15 Many health policy experts believe some types of health care services are overutilized. Where true, a quantity reduction arising from the practise of monopsony power might be viewed every bit beneficial. However, this paternalistic arroyo to consumption is not ordinarily adopted past antitrust enforcers.

16 R. Town and S. Liu, "The Welfare Bear upon of Medicare HMOs," RAND Periodical of Economics, Winter 2003 34(iv):719–36.

17 See, for example, Thousand. Gaynor and R. Boondocks, The Impact of Infirmary Consolidation (Princeton, Due north.J.: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, June 2012), http://world wide web.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2012/06/the-bear upon-of-hospital-consolidation.html.

18 Southward. Sheingold, N. Nguyen, and A. Chappel, "Competition and Pick in the Health Insurance Marketplaces, 2014–2015: Impact on Premiums," ASPE Issue Brief (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Wellness and Homo Services, July 30, 2015), http://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/competition-and-choice-health-insurance-marketplaces-2014-2015-impact-premiums.

nineteen L. Dafny, K. Duggan, and S. Ramanarayanan, "Paying a Premium on Your Premium? Consolidation in the U.S. Health Insurance Industry," American Economic Review, Apr 2012 102(2):1161–85.

twenty Z. Song, M. B. Landrum, and Grand. E. Chernew, "Competitive Bidding in Medicare: Who Benefits from Competition?" American Journal of Managed Care, Sept. 2012 xviii(9):546–52.

21 E. Eastward. Trish and B. J. Herring, "How Do Wellness Insurer Market Concentration and Bargaining Power with Hospitals Affect Health Insurance Premiums?" Journal of Wellness Economics, July 2015 42:104–xiv.

22 J. R. Guardado, D. W. Emmons, and C. Thou. Kane, "The Price Effects of a Large Merger of Health Insurers: A Case Study of UnitedHealth-Sierra," Health Direction, Policy and Innovation, June 2013 ane(3):16–35.

23 This is a specially salient bulwark because of the craven-and-egg problem of insurer–provider negotiations. Providers are mostly willing to offer the near competitive rates to insurers with a large market share; however, to gain market share an insurer needs to offer low premiums (and to do so sustainably, must have competitive provider rates).

24 L. Dafny, J. Gruber, and C. Ody, "More Insurers, Lower Premiums: Show from Initial Pricing in the Health Insurance Marketplaces," American Journal of Health Economics, Wintertime 2015 1(1):53–81.

25 M. J. Dickstein, M. Duggan, J. Orsini et al., "The Impact of Market Size and Composition on Health Insurance Premiums: Show from the First Year of the Affordable Care Act," American Economic Review, May 2015 105(5):120–25.

26 See, for example, CNBC, "Aetna, Humana CEOs Talk Antitrust Concerns," July six, 2015, http://video.cnbc.com/gallery/?video=3000394309.

27 M. J. McCue and M. A. Hall, The Federal Medical Loss Ratio Rule: Implications for Consumers in Year 3 (New York: The Commonwealth Fund, March 2015), p. 9.

28 For case, run into Aetna'south printing release announcing the acquisition of Humana: "The combination will provide Aetna with an enhanced ability to work with providers and create value-based payment agreements that event in meliorate intendance to consumers, and spread cutting-edge clinical practices and quality care." Aetna, "Aetna to Acquire Humana for $37 Billion, Combined Entity to Bulldoze Consumer-Focused, Loftier-Value Health Intendance," July iii, 2015, https://news.aetna.com//news-releases/aetna-to-learn-humana-for-37-billion-combined-entity-to-drive-consumer-focused-high-value-wellness-care/.

Source: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2015/nov/evaluating-impact-health-insurance-industry-consolidation

0 Response to "Development of the Modern Health Insurance Industry Peer Reviewed"

Post a Comment